Fall is the time of year when I like to dream big. There’s something about autumn’s crisp mornings that makes me want to plan, create and renovate. Take the change of season and mix in a pinch of guilt from spending lazy summer days on crab decks, and I’m ready to chart a productive course for the long wintry months ahead. Yet once my goals and dreams are set, I often wonder which will come to fruition and which will die on the vine.

A few weeks ago, our son had a soccer game in Leonardtown and we thought this was a good opportunity to tap into Southern Maryland’s rural scenery and get inspired by the Bay’s shift into Fall. We’d see the red perfection of late-season steamed crabs match the first blush of crimson maple leaves sparking color into the landscape. And local wild oysters would be growing plump and poised for slurping.

The soccer match began at 5:30, so we had the whole day to ourselves. We cruised down Route 301 past Amish farms, run-down motels and dry cornfields hoping to be turned into mazes. Just north of the Gov. Harry Nice Memorial Bridge, my husband Bill told me to stop the car and pointed across a field. WTF is that? I saw the remains of a castle overrun with weeds and ivy. A dilapidated sign with peeling paint heralded, “Aqua-Land.”

The soccer match began at 5:30, so we had the whole day to ourselves. We cruised down Route 301 past Amish farms, run-down motels and dry cornfields hoping to be turned into mazes. Just north of the Gov. Harry Nice Memorial Bridge, my husband Bill told me to stop the car and pointed across a field. WTF is that? I saw the remains of a castle overrun with weeds and ivy. A dilapidated sign with peeling paint heralded, “Aqua-Land.”

Curious, we left the highway to investigate. While we walked around the crumbling portico and rusty turrets, Bill whipped out his cell phone and found an old article about Aqua-Land in the Baltimore Sun. We learned that in the late 1950s two brothers, Dennis and Delbert Conner, had big dreams to build a grand casino and amusement park on the Potomac River. They opened Aqua-Land in 1960.

According to the article, “Flights with free champagne brought Washington and Baltimore visitors to an airstrip at Cliffton for 24 unreal hours. Tigers and bears prowled in a petting zoo, a giant Humpty Dumpty welcomed visitors to the children’s theme park,  Storyville U.S.A., and guests traversed the grounds via mini-trains. The Conners dreamed of creating a ‘Las Vegas of the East’ and building thousands of homes at their Cliffton on Potomac community alongside it. If visitors bought lots and stayed for good, the Conner brothers gave them free kitchen utensils.”

Storyville U.S.A., and guests traversed the grounds via mini-trains. The Conners dreamed of creating a ‘Las Vegas of the East’ and building thousands of homes at their Cliffton on Potomac community alongside it. If visitors bought lots and stayed for good, the Conner brothers gave them free kitchen utensils.”

Unfortunately, the deck was stacked against Aqua-Land. PEPCO built a monstrosity of a power plant on the other side of Route 301 across from the gambling palace. Then the county rejected Conners’ permit to dig a moat around the Jungle-Land animal attraction. The final nail in the coffin was when Maryland began phasing out slot machines in 1963.

With heavy hearts and broken dreams, Dennis and Delbert sold Aqua-Land in 1972. Today a campground and marina have replaced the resort where Humpty Dumpty once watched crowds from on top of his wall. We took a spin around, hoping to discover ruins from Aqua-Land’s glory days.

No such luck. RVs and trailers were scattered beneath oak trees. Scrawny cats with mangy pelts chased field mice through unraked leaves. A basketball hoop with a rusty chain net and an overturned picnic table implied the fun was done for the season – if not the foreseeable future. Campers facing south had a view of the Potomac River; those looking east watched smokestacks billowing fumes from the PEPCO plant. In all fairness, it was the off-season, so maybe things picked up during the Summer.

No such luck. RVs and trailers were scattered beneath oak trees. Scrawny cats with mangy pelts chased field mice through unraked leaves. A basketball hoop with a rusty chain net and an overturned picnic table implied the fun was done for the season – if not the foreseeable future. Campers facing south had a view of the Potomac River; those looking east watched smokestacks billowing fumes from the PEPCO plant. In all fairness, it was the off-season, so maybe things picked up during the Summer.

We continued south over the Nice Bridge for a quick dip into Virginia to grab lunch. As we sped past discount tobacco shacks, tiny Baptist churches and chicken processing plants, we mused over the challenges restaurants and small businesses face on the Bay. Merciless storms, economic turns or simply bad luck can crush the best-laid plans. Somehow many survive – even flourish – and keep their dreams alive.

We landed in Colonial Beach, a quaint resort town known for its 2.5-mile beach and some of the Bay’s best seafood. Our destination: Denson’s Grocery and R&B Oyster Bar. Its modest exterior didn’t prepare us for what we found inside. The moment we stepped through the door, we knew we’d discovered a gem.

We landed in Colonial Beach, a quaint resort town known for its 2.5-mile beach and some of the Bay’s best seafood. Our destination: Denson’s Grocery and R&B Oyster Bar. Its modest exterior didn’t prepare us for what we found inside. The moment we stepped through the door, we knew we’d discovered a gem.

Inside the market, the smell of blueberry pancakes for breakfast mingled with the aroma of Maryland crab soup. Most country stores we find are stocked with bait, fishing tackle, canned goods, and generic sundries. These shelves were a foodie’s delight, harboring everything from Spanish olives to Southern grits. The refrigerated cases held Boar’s Head meats, fresh local fish, and upscale beer and wines.

We were seated in the oyster bar, a screened-in structure with unfinished wood and patio furniture. With a smile that lit up the room, the owner greeted everyone by first name as if we were guests in his home. He told us how he left the button-down business world to build a local market, just like his father and grandfather had. His passion for oysters drove him to add on the rustic oyster bar. It was a gamble, but he had to give it a go. We felt like his dream was coming true, as the place bustled with jovial customers. He presented a tray of Sewansecott and Chincoteague oysters, which we downed before our crab cake and oyster po’ boy arrived. As we soaked up the homey atmosphere, we felt confident that Denson’s would be cranking out great food next time we rolled into town.

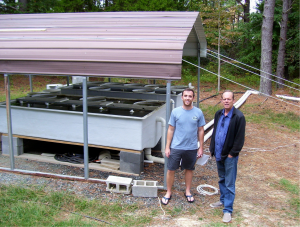

Fighting the urge to linger longer, we set our GPS for one more stop before the soccer match. Our next destination was True Chesapeake Oyster Co. to hook up with the owner, Pat Hudson, for a tour of his aquafarm overlooking St. Jerome Creek in Ridge, MD. Hudson, along with hundreds of other entrepreneurial watermen around the Bay, has developed ingenious new techniques for cultivating oysters. The industry is booming. Bivalves are growing by the millions in cages on the Bay and its tributaries, and they’re cleaning up the waters and putting Chesapeake oysters back on the world culinary stage.

Our first stop was a nursery of sorts, where tiny infant oysters called “spats” lounged in tanks that were filled with a formula of nutrients and algae designed just for them. Pat gently pulled a handful of about 30 youngsters from their watery cribs for our inspection. Almost the size of a pea, these mini oysters were a wondrous sight to behold.

When they grow larger, the fledgling oysters are moved into metal cages that rest on the Bay’s floor, protected from poachers and predators such as crabs, stingrays and other hungry creatures. Under the watchful eyes of Pat and his aquafarming colleagues, the oysters reach the legal market size of 3 inches in a year or so.

Along the way, each oyster filters around 50 gallons of water daily, removing harmful elements from the Bay’s shores and creating a healthier habitat.

Along the way, each oyster filters around 50 gallons of water daily, removing harmful elements from the Bay’s shores and creating a healthier habitat.

On our way out, we stopped for a moment to marvel at the stunning view of True Chesapeake Oyster Co. and the dawning of a new era for the Bay’s oysters.

Pat and his fellow aquafarmers are dreaming big. They’re resurrecting a bruised and battered species from centuries of irresponsible harvesting, disease and pollution. If they succeed, their dreams will make us the grateful beneficiaries of a cleaner Bay and robust oysters for our dinner table.

When we arrived at the field, the soccer game had just begun. I looked out at my son and wondered what he was thinking. Did he imagine himself about to score the winning goal at a future World Cup match? Or was he just being a kid kicking a ball around with his team? You never know in Southern Maryland. The place is packed with dreamers, each hoping for a shot at success.