If someone tried to take away your plate of fresh Chesapeake oysters, would you shoot him? Well, you wouldn’t be the first person to react that way to an oyster thief. For decades, the Chesapeake Bay felt like the Wild West, where deadly boat chases and gunfights were commonplace along the shores. And this hotbed of conflict was over one innocent creature – the oyster.

During the Oyster Wars of the Chesapeake Bay, “Oysters were so valuable that we needed artillery to protect them from pirates,” says Jeff Holland, Executive Director of the Annapolis Maritime Museum. “It’s astonishing that people would kill each other over a bivalve.”

During the Oyster Wars of the Chesapeake Bay, “Oysters were so valuable that we needed artillery to protect them from pirates,” says Jeff Holland, Executive Director of the Annapolis Maritime Museum. “It’s astonishing that people would kill each other over a bivalve.”

For thousands of years, the Bay was a dream breeding ground for oysters. English settlers in the early 1600s were amazed by 12-inch long oysters and beds so large that ships would run aground on them. Captain John Smith ate them. George Washington relished them. And as America grew, so did oysters’ popularity. By the late 1700s, Chesapeake oysters were served on tables from Norfolk to Boston.

Oysters were growing like weeds in the Bay, and Americans from presidents to paupers were eating them like hot cakes. What could possibly go wrong? Things started to go awry in the early 1800s when over-harvesting in New York, Rhode Island, and Connecticut depleted their oyster population, and Northerners started licking their chops over the Chesapeake’s bounty. When New England oyster boats floated into the Bay looking for fresh waters to plunder, locals did not hang up a welcome sign. To protect their treasure of oysters from Yankee intruders, Maryland and Virginia passed laws that only allowed fishing by local residents.

By the mid-1800s, a boom time was underway, and everybody wanted a piece of the action. Thanks to a new steam-canning process, people as far away as the Pacific Coast and Colorado gold mines were gobbling up Chesapeake oysters that were delivered long-distance by train. Baltimore became the oyster-packing epicenter with over 100 processing houses along its harbor. Shipbuilders in Oxford and Annapolis cranked out new watercraft to meet rapidly growing demand.

Sleepy waterfront towns like Cambridge and Solomons turned into bustling ports built upon discarded oyster shells. When railroad tracks extended down the Eastern Shore to Crisfield, the town erupted with oyster shucking plants, brothels, and saloons packed with thirsty workers and watermen. Fistfights and alcohol disrupted civil society.

The Bay and its rivers became jam-packed with skipjacks and boats of all shapes and sizes, and the oyster supply seemed endless. “By 1875, a total of 17 million bushels was removed from the Chesapeake, yet harvesting continued to increase. At its peak in the mid-1880s, over 20 million bushels of oysters were taken from the Bay each year,” reports Dr. Henry M. Miller, Director of Research at Historic St. Mary’s City. And when a massive oyster reef was discovered in Tangier Sound, things started to heat up.

With such a plentiful resource, you’d think there’d be enough for everyone. Instead, a “get what you can before it’s gone” mentality took over, and people who had co-existed somewhat peacefully got mired in heated turf wars. Clashes occurred over who could harvest oysters. In shallow areas, watermen leaned over their boats using long wooden tongs to lift their catch from the water by hand. In deep waters, large ships pulled dredges with iron teeth along the bottom making a clean swipe over oyster beds.

With such a plentiful resource, you’d think there’d be enough for everyone. Instead, a “get what you can before it’s gone” mentality took over, and people who had co-existed somewhat peacefully got mired in heated turf wars. Clashes occurred over who could harvest oysters. In shallow areas, watermen leaned over their boats using long wooden tongs to lift their catch from the water by hand. In deep waters, large ships pulled dredges with iron teeth along the bottom making a clean swipe over oyster beds.

Maryland allowed dredging as long as ships stayed away from the shore and river beds. When dredgers ignored the laws and invaded the tongers’ space, big problems started brewing. To protect their oysters and livelihood, tongers appealed to Annapolis for help, but the lackluster response forced them to handle matters on their own. Gunfights, unruly water disputes, and dead bodies of watermen floating on the shores became regular events.

To make matters worse, the border between Maryland and Virginia wasn’t clearly marked or well-defined. So, when Virginia watermen heard about the plethora of oysters in places like Tangier Sound or Eastern Shore rivers, they felt they had a right to them. Maryland oystermen heartily disagreed.

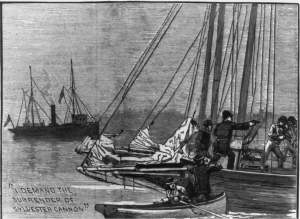

Violence and anarchy escalated to such a point that somebody had to step in. In 1868, the Maryland Oyster Police Force was formed, with Hunter Davidson elected as its first commander. He received a side-wheeled steamboat named Leila to restore order. Not a fleet of boats – just one. While you cruise around the Bay with all its hidden inlets, imagine policing that expansive area with just one boat.

“The Oyster Police were outnumbered but still put up a valiant fight,” reflects Jeff Holland of the Annapolis Maritime Museum. “In one incident, a dozen illegal dredging schooners chained their boats together and floated defiantly on the Choptank River. When this rag-tag flotilla reached rifle range and prepared to shoot, the Oyster Police steamer barreled forward and rammed those schooners like a bowling ball.” Two ships were sunk; two were taken captive.

The Oyster Police added more ships, including the Avalon, Mary Compton, and Governor McLane, and armed them with stronger firepower. But the oyster pirates remained bold and brazen. One foggy night in 1888, the Corsica carried passengers and mail from Baltimore to Chestertown. A notorious oyster pirate named Gus Rice thought it was an Oyster Police steamer and opened fire. Innocent women and children scrambled to the cabin floors narrowly escaping the dredgers’ relentless spray of bullets.

Dredgers moved through the Chesapeake with cold efficiency and short-sightedness. They stripped more oysters than the Bay could produce and then plundered the tributary rivers. The Oyster Police caught some pirates, but many dredgers worked at night posting lookouts to watch for patrol boats. The Little Choptank River was especially hard hit and lost thousands of oysters a day to dredgers. When Cambridge formed a militia to defend its oyster bars, dredgers fired on the town and promised to torch the entire city if they met resistance again.

Dredgers moved through the Chesapeake with cold efficiency and short-sightedness. They stripped more oysters than the Bay could produce and then plundered the tributary rivers. The Oyster Police caught some pirates, but many dredgers worked at night posting lookouts to watch for patrol boats. The Little Choptank River was especially hard hit and lost thousands of oysters a day to dredgers. When Cambridge formed a militia to defend its oyster bars, dredgers fired on the town and promised to torch the entire city if they met resistance again.

By the 1890s, the Bay’s oyster population fell into steep decline, and in 1900 more oyster packing houses closed on the Bay than opened. Over-harvesting brought the annual yield to around 3 million bushels in the 1920s. During World War I, many boats were used in America’s defense, and during Prohibition rumrunning became a lucrative pastime for watermen.

The Oyster Wars had one final skirmish in store before coming to an end, and the incident took place at a quiet waterfront town called Colonial Beach. If you’ve ever taken a boat up the Potomac River, you might have noticed a funky border between Virginia and Maryland. Dating back to colonial times, Virginia’s state line ends at the southern shore, and Maryland has the rights to the Potomac. That means oysters in the Potomac belong to Maryland.

In 1942 – decades after the Bay’s oyster population had plummeted – a vast bed was discovered on Swan Point along the Potomac. Maryland police had a tough time protecting their state’s treasure, because many of its boats were busy in World War II and Virginia watermen couldn’t resist plucking the valuable bivalves from the river. By the late 1940s, oyster pirating kicked into high gear, and Virginia dredgers – nicknamed the “Mosquito Fleet” – buzzed away from Maryland police in high-speed power boats.

Gunfights and dramatic chase scenes resumed between Virginia daredevils and frustrated Oyster Police, now armed with rifles and machine guns. By the late 1950s, the pot was ready to boil over. One night in 1959, a Virginian named Berkeley Muse decided to dredge oysters with his buddies. When they realized they’d been spotted by a police boat, they sped toward the safety of Monroe Bay in Virginia. Maryland police took off after Berkeley and his gang, and bullets started flying. Poor Berkeley was hit in the chest and bled to death at dawn in his boat on the shore of Colonial Beach.

This death of a waterman over oysters was the last straw. The two states worked out legislation that eased tensions, and after nearly a century of bloody conflicts, the Chesapeake Oyster Wars were over.